Craniofacial

Trauma

Although facial fractures are less common in children than in adults, they can be associated with significant morbidity and disability. Pediatric facial fractures are often due to severe traumatic mechanisms, so care should be taken to evaluate for associated injuries such as airway, intracranial, cervical spine, ocular, and dental injuries.

Pediatric Considerations

The likelihood of specific injuries differs in younger children due to the changing anatomy and physiology of the developing face:

-

At birth, the skull is relatively much larger than the face. As a result, children <5 yo tend to sustain cranial rather than facial injuries.

-

Progression of sinus pneumatization:

Ethmoids

Sphenoid

Maxillary (begins at 3-5 yo)

Frontal (begins at 5-10 yo)

Maxillary and frontal sinus development are correlated with midface fractures.

-

Deciduous teeth erupt at 6 months of age and adult dentition is reached by 12 years of age.

-

Elastic bones reduce the risk of Lefort fractures. Oblique and greenstick fractures are more common.

Fat pads and soft tissues cushion the bones, thus reducing displaced fractures.

Young children (<6 years) are more likely to have frontal fractures occur due to falls. This age group has the lowest rates of facial fractures.

As children age, midface and mandible fractures become more common.

Facial fractures in older children (>6 years) commonly occur due to play, sports, MVCs, and assault.

Evaluation

Step 1: Primary Assessment

Assess the patient's airway, breathing, and circulation are intact. Any life-threatening conditions, such as airway obstruction or severe bleeding, must be addressed promptly.

Step 2: History Taking

Ask about the mechanism of injury, time elapsed since the event, and any associated symptoms. Information about the force of impact, direction, and type of object involved can help assess the likelihood of various types of injuries.

Step 3: Physical Examination

Perform a comprehensive physical examination of the face, including the forehead, eyes, nose, cheeks, lips, and jaw. Carefully observe for asymmetry, deformities, lacerations, or any signs of bruising. Assess the overall facial expression and evaluate for CN5 and CN7 function. Gently palpate the bony structures, particularly the maxilla, mandible, and zygoma, checking for tenderness, crepitus, or step-offs. Take note of any mobility or instability of these structures. For specific considerations see below:

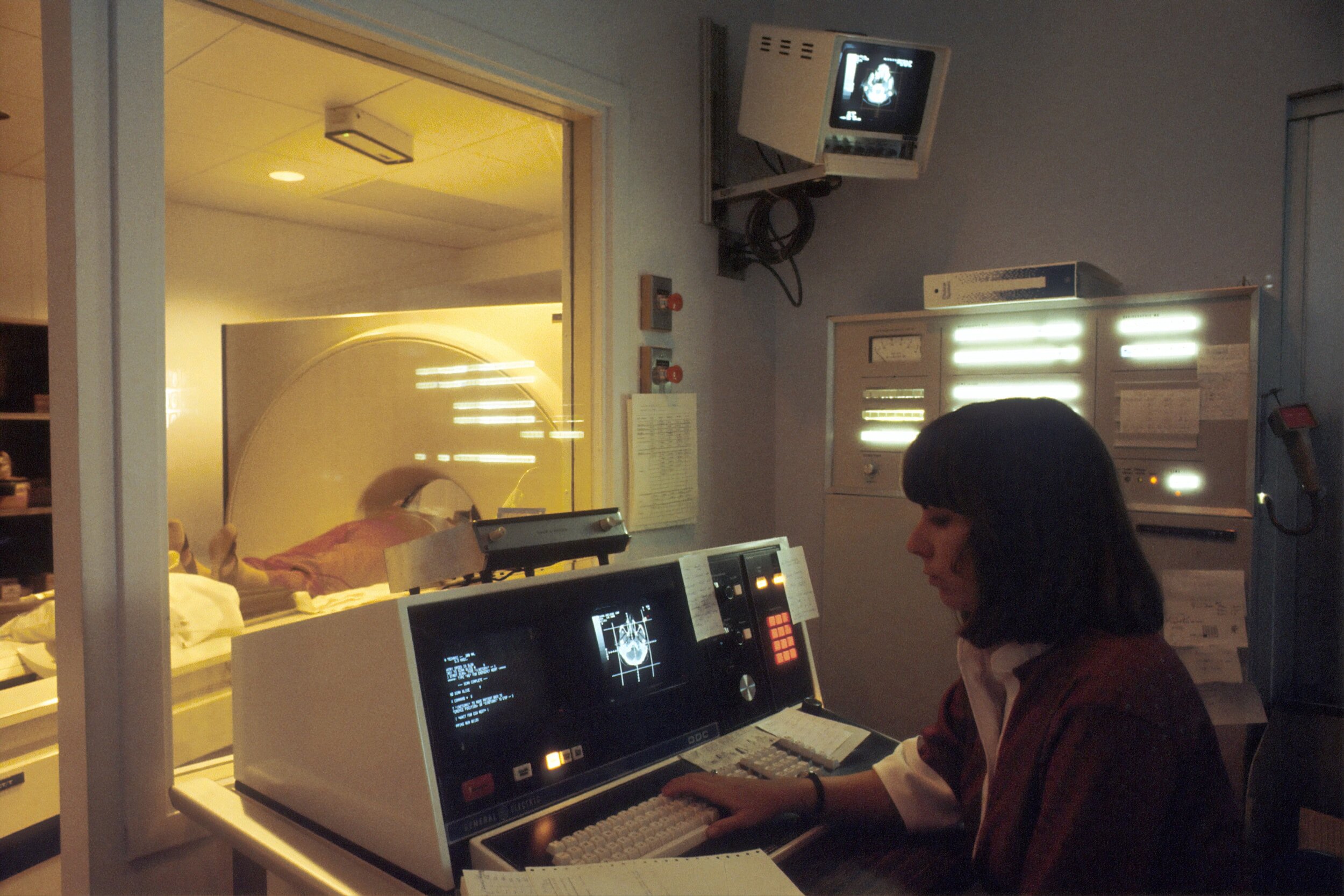

CT maxillofacial without contrast is the gold standard for viewing craniofacial injuries as it has a greater ability to detect fractures and visualize soft tissue injuries.

References

Berlin RS, Dalena MM, Oleck NC, Halsey JN, Luthringer M, Hoppe IC, Lee ES, Granick MS. Facial Fractures and Mixed Dentition - What Are the Implications of Dentition Status in Pediatric Facial Fracture Management? J Craniofac Surg. 2021 Jun 1;32(4):1370-1375. doi: 10.1097/SCS.0000000000007424. PMID: 33427769.

Braun TL, Xue AS, Maricevich RS. Differences in the Management of Pediatric Facial Trauma. Semin Plast Surg. 2017 May;31(2):118-122. doi: 10.1055/s-0037-1601380. PMID: 28496392; PMCID: PMC5423796.

Cole P, Kaufman Y, Hollier LH Jr. Managing the pediatric facial fracture. Craniomaxillofac Trauma Reconstr. 2009 May;2(2):77-83. doi: 10.1055/s-0029-1202592. PMID: 22110800; PMCID: PMC3052668.

Koch BL. Pediatric considerations in craniofacial trauma. Neuroimaging Clin N Am. 2014 Aug;24(3):513-29, viii. doi: 10.1016/j.nic.2014.03.002. Epub 2014 May 21. PMID: 25086809.

Rogan DT, Fang A. Pediatric Facial Trauma. 2022 Jul 25. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2023 Jan–. PMID: 32644358.

Shaw KN Bachur RG. Fleisher & Ludwig's Textbook of Pediatric Emergency Medicine. 7th ed. Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer; 2016.